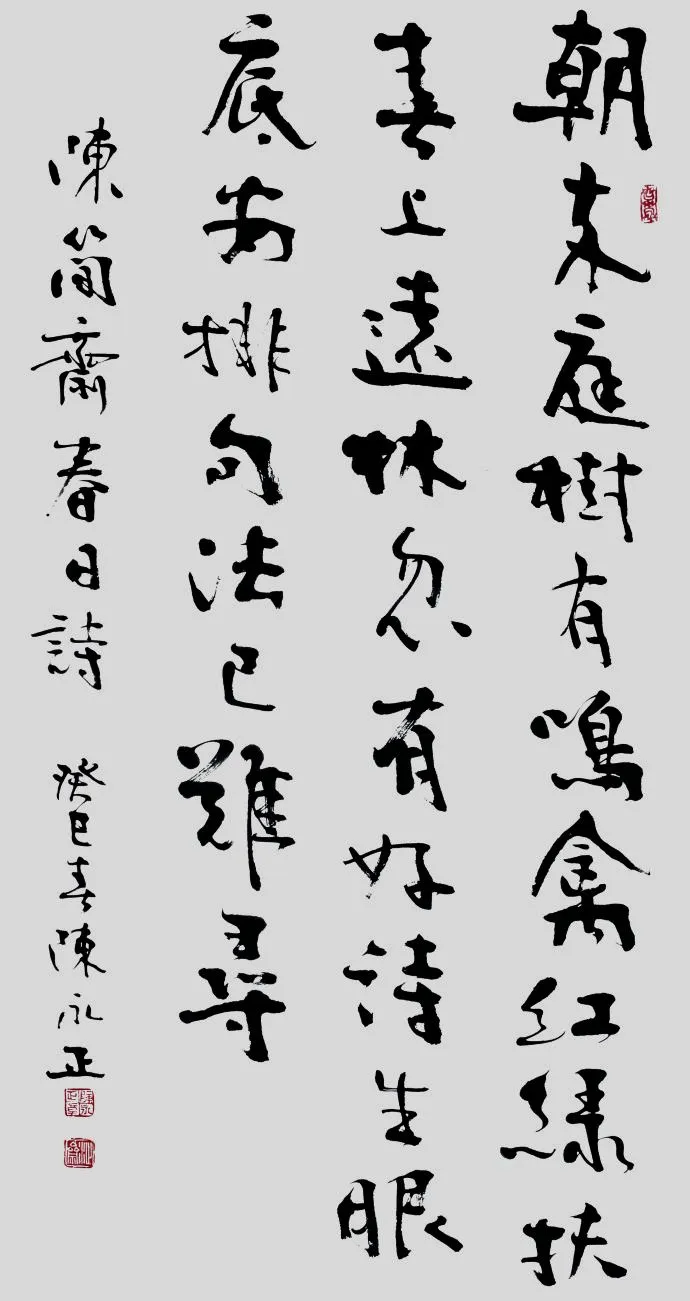

陈永正,粤西高州人,字止水,号沚斋。生于寒门,然秉性恬淡,性喜古艺。其书法融篆、隶、楷、行、草于一炉,脱凡俗形迹,自成雅趣。此为创新,亦为返本,别出机杼。早岁陈公曾执教羊城三十六中,擅长诗文,学识渊博,教书育人,颇有建树。然其人未以书艺为业,反以学问修身,功底深厚。故于书法,非徒流于技艺,乃兼涵古今,得字外真功,书作愈显独特新颖。或谓其书近江湖体,殊不知此乃游于古法之外,融通百家,革故鼎新,自成格局者也。

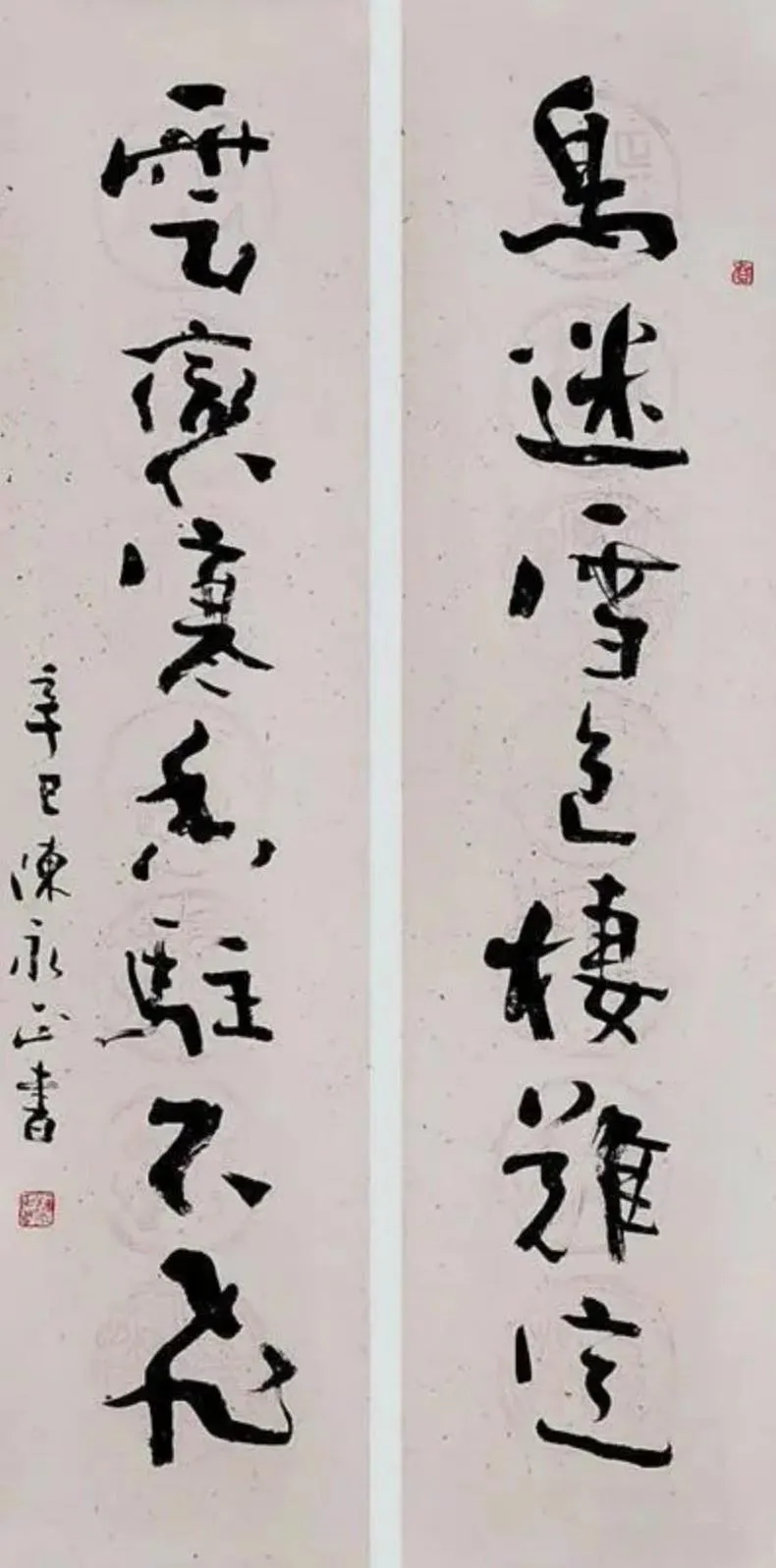

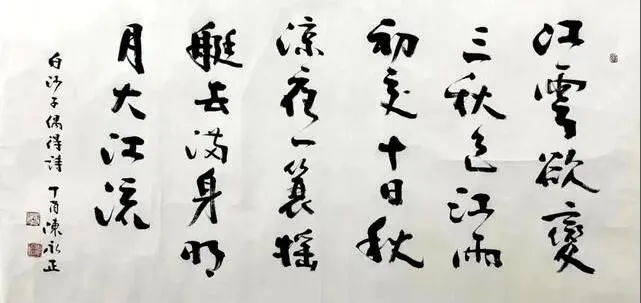

其笔墨挥洒,篆隶楷草合而为一,既有楷法之端整,又兼篆隶之波磔,行书之飞动。点画紧凑,线条婉转如春水,笔意流畅而灵动。其间顾盼相宜,妙于呼应,字形参差错落,章法自成天趣。布局疏密相生,大小不拘规矩,而尽显错综之妙,含蓄雅致,融古意于新法中,令人观之神悦心畅,正所谓以古为基而不拘于古者也。陈永正尝言书法之妙,关乎书者之品性与意趣。其言书家成就,必赖二端:一则于传统有深厚功力,非止形似,尤重神领;二则于承继中寻得新意,革故鼎新,始为上乘。陈氏又谓,书家之成,德、才、学、视四者并举为要。德者,涵养也;才者,天资也;学者,博闻广识也;视者,鉴赏力也。若无鉴力,则无从辨优劣,学无所循,所谓从善择高,正是考其眼界见识耳。

陈公于书风自有追求,谓“古雅清刚”为其志趣所在。所谓“古雅”,乃文人之韵,清逸不俗;“清刚”者,风骨凛然,雄健中正。此风格,乃其天赋、修养与学识所致,亦为其独到审美之结晶。书家必当选与己气质相契者,方能有得,成就卓然。论及学书之法,陈氏素言,临帖为学书之首途,未临帖者,犹在门外徘徊。少时学书,初未得其法,直至十九岁遇李天马先生,方知其中奥妙。李公启之笔意,授其结体之规,陈氏由此入书道正轨。其后多临碑帖,尤重褚遂良《枯树赋》,反复摹写,渐悟其中精义,久而成己书,终有独见。

陈永正于书道,多受前贤之泽。李天马授以书规,开其用笔之窍;欧潜云不时切磋,促其步步精进;朱庸斋行书中自见文人清雅,令陈公神会其中妙旨。容庚、商承祚笔法严谨,陈公亦从中体悟,书作自此更加含蓄收敛,愈加见功力之厚。诸先辈之教诲,潜移默化,陈公由此书艺大进,学问修养亦随之日增。论及今之文坛,陈永正感世有“专家”而少文人,诚为叹息。古之文人,不独通于书道,亦精于政事、诗文、收藏等艺。以容庚、商承祚为例,二老既为学问大家,亦为书家,且为社会所重。自度犹有不足,未敢妄称文人。西学自入,虽于科学有所裨益,然于文学艺术,陈公坚守中原之道,毋使外法易己。文道之传,宜从其源流而探,不可轻易附会外学。此言四十载如一日,未尝有移。

谈及当代书坛,陈公以为虽繁荣有象,然普及与精进皆尚未尽,故劝书家多行普及之事,书法展览应与民同庆,宜于节庆时入基层,挥毫示艺。又谓书法家当固本求新,合于民意者方能传世。有天资者,尤应不拘一格,于古法之基上求新变,方可自立于世,得真名家之风骨。陈永正论“丑书”之风,持慎重态度,分为两途。一为江湖俗笔,未有根基,漫涂乱书,法度不存,宜加摒弃;一为求变而成,虽时有拗拙之象,然或于岁月沉淀中见古意,然此类不当倡于世间。陈公劝书家当备两途,一为探求自家风貌,于创新中见个性;一为体民意所喜,作雅正之笔,以合众情。

陈公于书道,根于传统而不拘形迹。常言书非仅技艺显扬,实为文化涵养所发,书家之功,不在技法之尽善,乃在其上更追高境。惟此,方可得其道,成其艺。

Chen Yongzheng: Blending Ancient Ideas with New Methods, Embracing Tradition and Personal Ambition

Chen Yongzheng, a native of Gaozhou in western Guangdong, goes by the courtesy name Zhishui and the studio name Zhizhai. Born into humble beginnings, he exhibited a calm disposition and a natural fondness forical arts. His calligraphy blends seal script, clerical script, regular script, running script, and cursive script, transcending conventional forms to create his own refined aesthetic. This is not only an innovation but also a return to the fundamentals, standing out with originality.In his youth, Chen served as a teacher at Guangzhou's No. 36 Middle School, excelling in poetry and literature, with extensive knowledge and accomplishments in education. However, he did not make calligraphy his sole profession; instead, he refined his character through scholarship, building a deep foundation. Thus, his approach to calligraphy transcends mere technique, embracing both the ancient and modern, cultivating an understanding beyond the art itself. His works display increasing uniqueness and innovation. Some claim his style approaches that of "jianghu" (folk calligraphy), yet they fail to see that he roams beyond traditional boundaries, fusing various schools and innovating to establish a style uniquely his own.

His brushwork freely combines seal script, clerical script, regular script, and cursive script, presenting the upright structure of regular script while incorporating the dynamic strokes of seal and clerical scripts, along with the fluidity of running script. The strokes are compact yet graceful, like flowing spring water, with an effortless and lively rhythm. The characters harmonize with each other, forming a natural resonance, with varied shapes creating an interplay of contrast. The overall layout blends density and openness, with characters of different sizes arranged unpredictably, showcasing a subtle yet elegant charm. This seamless integration of ancient elements with innovative methods brings joy and delight to those who observe, embodying the principle of building on the past without being confined by it.Chen Yongzheng often remarked that the essence of calligraphy lies in the calligrapher's character and taste. He believed that success in calligraphy depends on two key factors: first, mastering traditional techniques deeply, not just in form but also in spirit; second, finding innovation through inheritance, breaking old conventions to create something new. He also stressed that a calligrapher's achievement relies on four qualities: virtue, talent, knowledge, and discernment. Virtue refers to cultivation, talent to innate ability, knowledge to broad scholarship, and discernment to aesthetic judgment. Without the ability to discern, one cannot distinguish between good and bad, nor can one learn effectively. Therefore, seeking out and studying the best works is a test of one's aesthetic vision.

Chen has long pursued a specific calligraphic style, one that he defines as "ancient, elegant, and clear-cut." "Ancient elegance" represents the refined grace of a scholar, free from vulgarity, while "clear-cut strength" embodies resolute spirit and firm integrity, with a bold and upright character. This style reflects his natural talent, cultivated demeanor, and extensive learning, as well as his unique aesthetic. A calligrapher must choose a style that aligns with their personal temperament to achieve true success.Speaking of the method of studying calligraphy, Chen frequently stated that practicing from ancient models is the first step in learning, and those who haven't done so are still lingering outside the gate. In his early years of learning, Chen didn't initially grasp the proper technique until he met Mr. Li Tianma at the age of nineteen, who unveiled the mysteries of calligraphy for him. Li taught him the principles of brushwork and character structure, setting Chen on the correct path in calligraphy. He later practiced from many stone rubbings and texts, particularly favoring Chu Suiliang's Kushu Fu, which he repeatedly copied. Over time, he gradually grasped its essence, eventually developing his own unique style.

Chen Yongzheng's calligraphy journey was greatly influenced by his predecessors. Li Tianma taught him the rules of calligraphy, unlocking the key to brushwork; Ou Qianyun constantly pushed him to progress step by step; and Zhu Yongzhai's running script embodied the refined elegance of a scholar, which deeply resonated with Chen. The precise techniques of Rong Geng and Shang Chengzuo further guided Chen, making his work more restrained and refined, displaying a deepening mastery. The teachings of these elders subtly shaped Chen's artistry, leading to significant advancements in both his calligraphic skills and his scholarly cultivation.Reflecting on the contemporary cultural landscape, Chen lamented that there are many "experts" but few true scholars, which he found regrettable. In the past, scholars were not only masters of calligraphy but also versed in politics, poetry, literature, and collecting. He cited Rong Geng and Shang Chengzuo as examples—both were not only scholars but also esteemed calligraphers and respected figures in society. Chen humbly admitted that he still fell short of such standards and did not dare to call himself a scholar. While he acknowledged the benefits of Western knowledge in science, Chen remained steadfast in preserving the Chinese cultural tradition in the realm of literature and art, resisting the influence of foreign systems. He believed that the transmission of literary and artistic traditions should be explored from within, rather than being easily substituted by external ideas—a view he has held unwaveringly for forty years.

Speaking of the contemporary calligraphy world, Chen believed that while it appeared to be flourishing, there was still room for improvement in both popularization and refinement. Therefore, he urged calligraphers to engage in efforts to popularize the art, suggesting that exhibitions should be held in conjunction with public celebrations, with calligraphy demonstrations offered at grassroots levels during festivals. He further asserted that calligraphers should establish a solid foundation in traditional techniques while seeking innovation, creating works that resonate with public taste in order to ensure their legacy. Those with exceptional talent, in particular, should break free from conventions and seek innovation based on traditional foundations, thereby establishing themselves with the true spirit of a master.Regarding the trend of "ugly calligraphy," Chen took a cautious stance, distinguishing between two types. The first consists of unrefined "jianghu" calligraphy, lacking foundation, with careless and chaotic strokes that disregard structure and should be rejected. The second type arises from the pursuit of innovation and may, over time, reveal a certain ancient charm, though it should not be widely promoted. Chen advised calligraphers to be prepared on two fronts: one, to explore their own personal style, expressing individuality through innovation; and two, to create works that align with public taste, composing elegant and proper calligraphy that resonates with the people.

Chen's approach to calligraphy is deeply rooted in tradition, yet unbound by conventional forms. He often emphasized that calligraphy is not merely the display of skill but the expression of cultural cultivation. The true achievement of a calligrapher does not lie solely in flawless technique, but in striving for a higher artistic realm beyond it. Only by doing so can one truly attain the essence of the art and achieve mastery.

责任编辑:苗君