黄胄,字映斋,讳梁淦堂,河北蠡县梁家庄人,生于民国十四年。自号黄胄,名噪华夏,工丹青,擅收藏,兼为卓著之社会活动家。癸酉之春,四月廿三日,溘然长逝于广州,享年七十有二。

Huang Zhou, courtesy name Yingzhai, given name Liang Gantang, was a native of Liangjiazhuang, Lixian, Hebei. He was born in the fourteenth year of the Republic of China. He later adopted the name Huang Zhou and became renowned throughout China. An accomplished painter and collector, he was also a distinguished social activist. On the twenty-third day of the fourth month in the year of Guimao, he passed away in Guangzhou at the age of seventy-two.

黄胄幼时八龄,尚寓乡里。幼读城隍庙中因果报应之壁画,时听母吴氏述二十四孝之传说。祖梁景峰,农暇乐唱戏;父梁建勋,初为乡塾之师,后参旧军,雅爱书画。此诸境遇,皆陶冶黄胄幼志,渐启其绘事之兴。甲申之年,投赵望云门下,潜心艺事,遂为大匠之基,奠乎此矣。

In his early years, Huang Zhou, at the age of eight, still resided in his hometown. As a child, he often viewed the murals depicting cause and effect in the Chenghuang Temple and listened to his mother, Wu, recount folk stories of the Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars. His grandfather, Liang Jingfeng, enjoyed singing opera during his leisure time from farming; his father, Liang Jianxun, initially a village teacher, later joined the old army and had a passion for calligraphy and painting. These influences cultivated Huang Zhou’s youthful aspirations and gradually kindled his interest in art. In the year of Jiashen, he apprenticed under Zhao Wangyun, diligently studying the art of painting, thus laying a solid foundation for his future as a grand master.

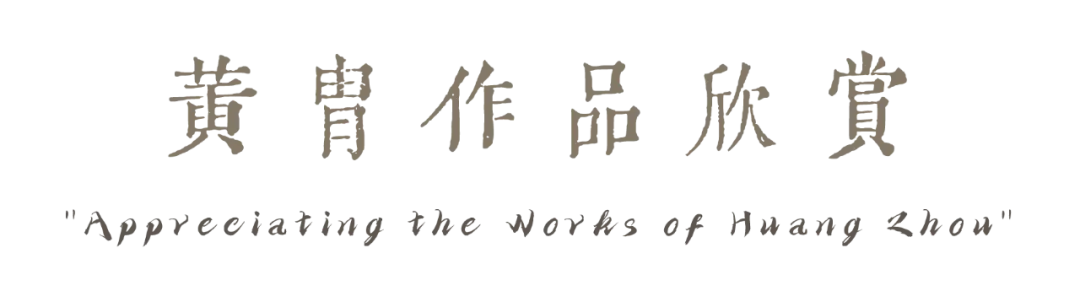

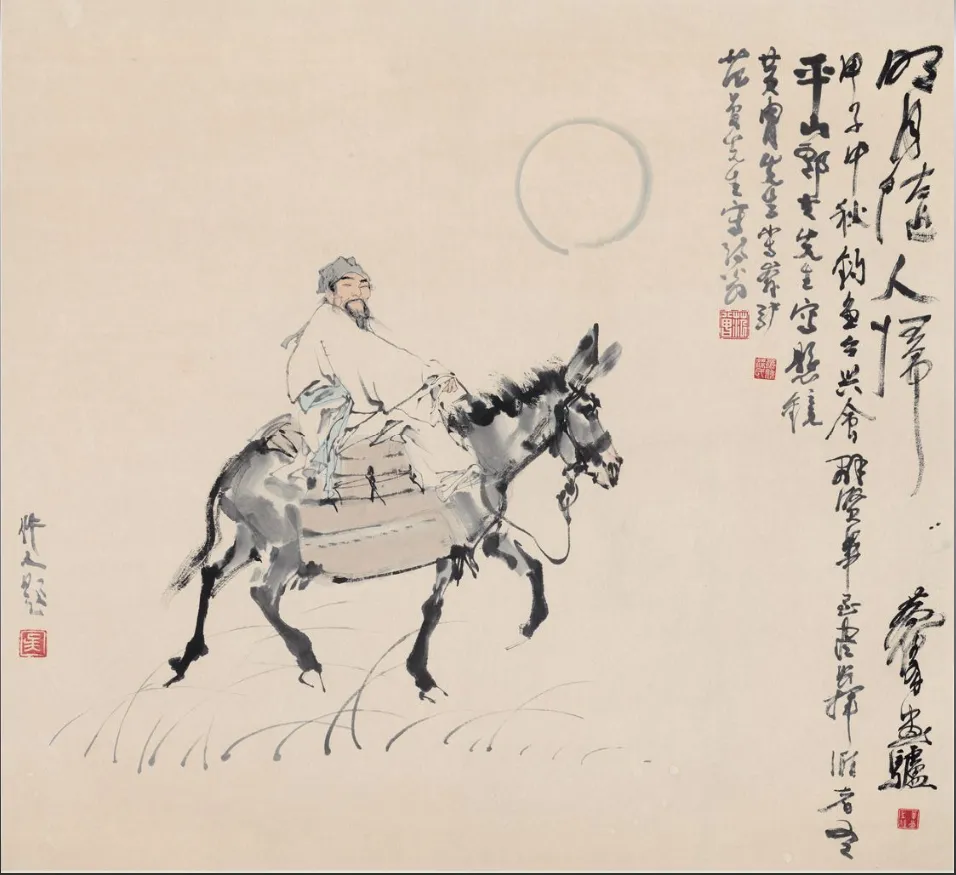

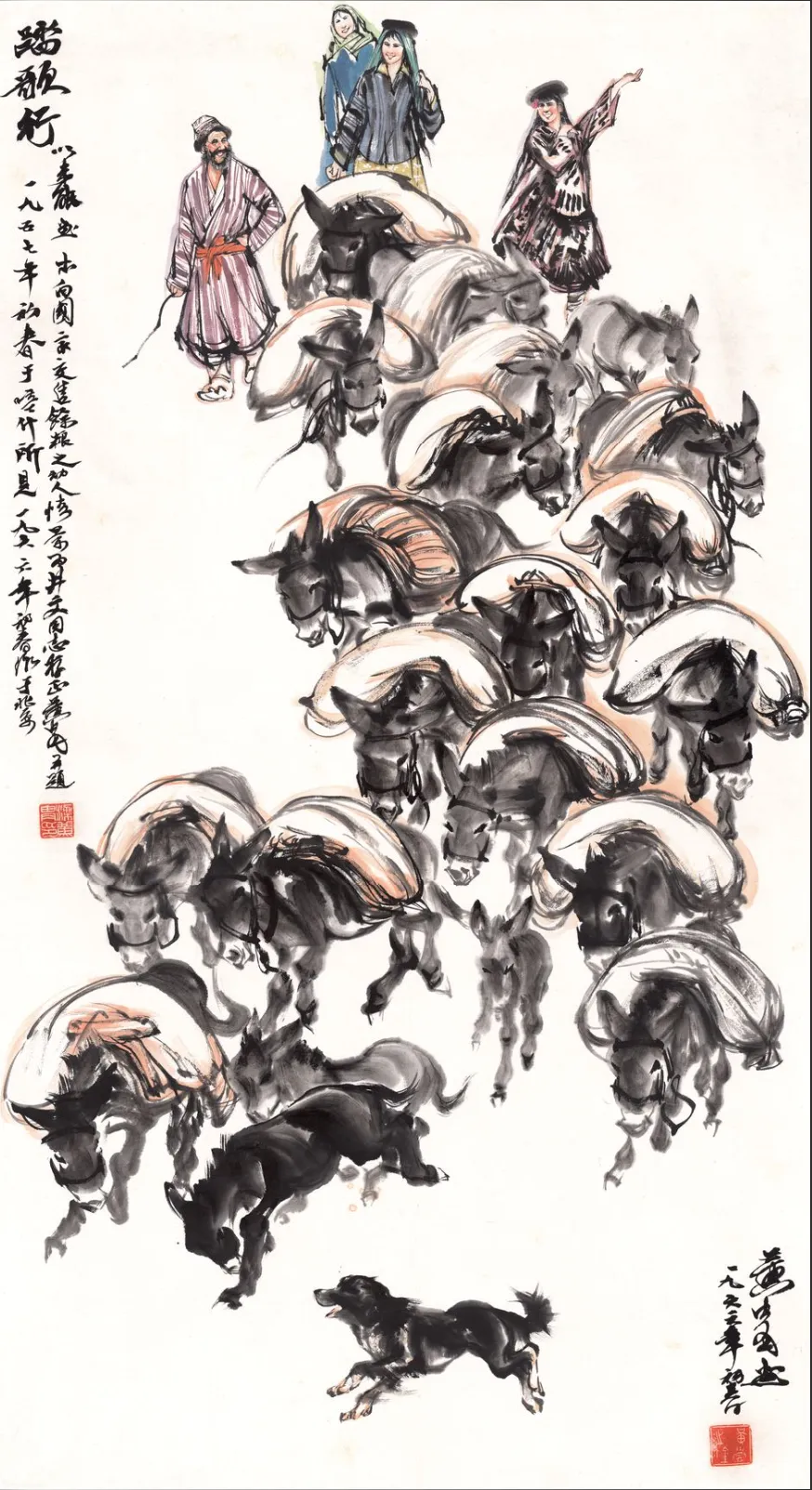

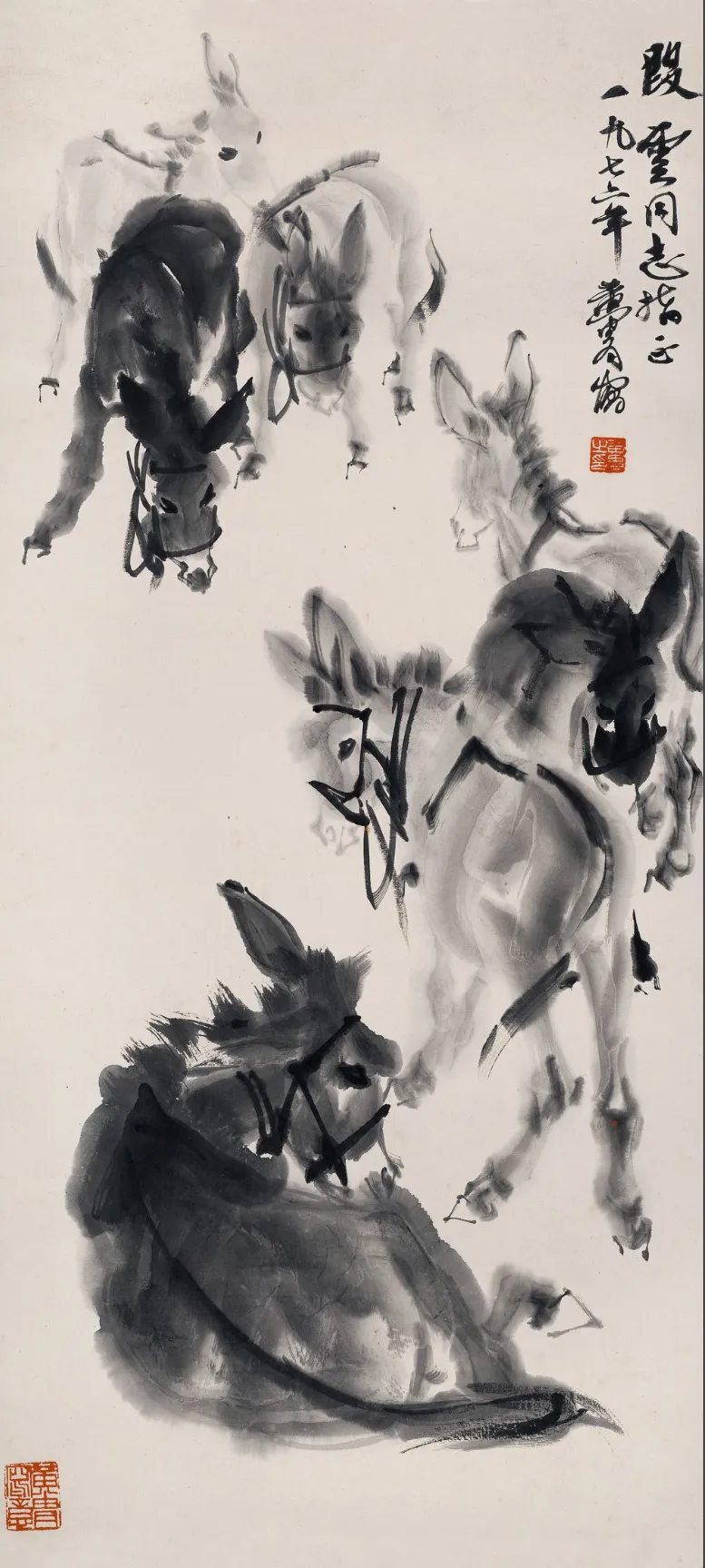

黄胄绘驴,乃其画艺之一绝。所绘之驴,形神毕肖,妙趣横生,笔简而意丰,繁冗之细节尽削,明暗之差异淡化,体积之感隐去,独现驴之生动,笔墨灵跃流畅。其技法精湛,笔势如风,墨色万变,简而精。黄胄之艺,取材于生活,表现于速写。以速写本,疾书新疆之民生景象,写情绘意。自谓:“画者无速写,不随时录真情,其艺将枯竭矣。”胄运笔如飞,擅捕人物、禽兽之神韵,线条流丽遒劲,风格奔放洒脱,诚为绝技。

Huang Zhou’s depiction of donkeys is one of his artistic excellences. The donkeys he painted were lifelike and full of charm, with simple yet expressive strokes that omitted unnecessary details, softened the contrasts of light and shadow, and de-emphasized volume, highlighting the vividness and fluidity of the lines. His technique was exquisite, his brushwork swift, and his use of ink varied and precise. Huang Zhou’s art drew inspiration from life and was expressed through sketching. He used sketchbooks to rapidly document the lives of the people in Xinjiang, capturing their essence and emotions. He proclaimed, “A painter without a sketchbook, who does not constantly record his genuine feelings from life, will see his artistic life wither.” Huang Zhou’s brush moved swiftly, adeptly capturing the essence of figures and animals, with fluent and powerful lines, and a style that was unrestrained and exuberant, truly an extraordinary skill.

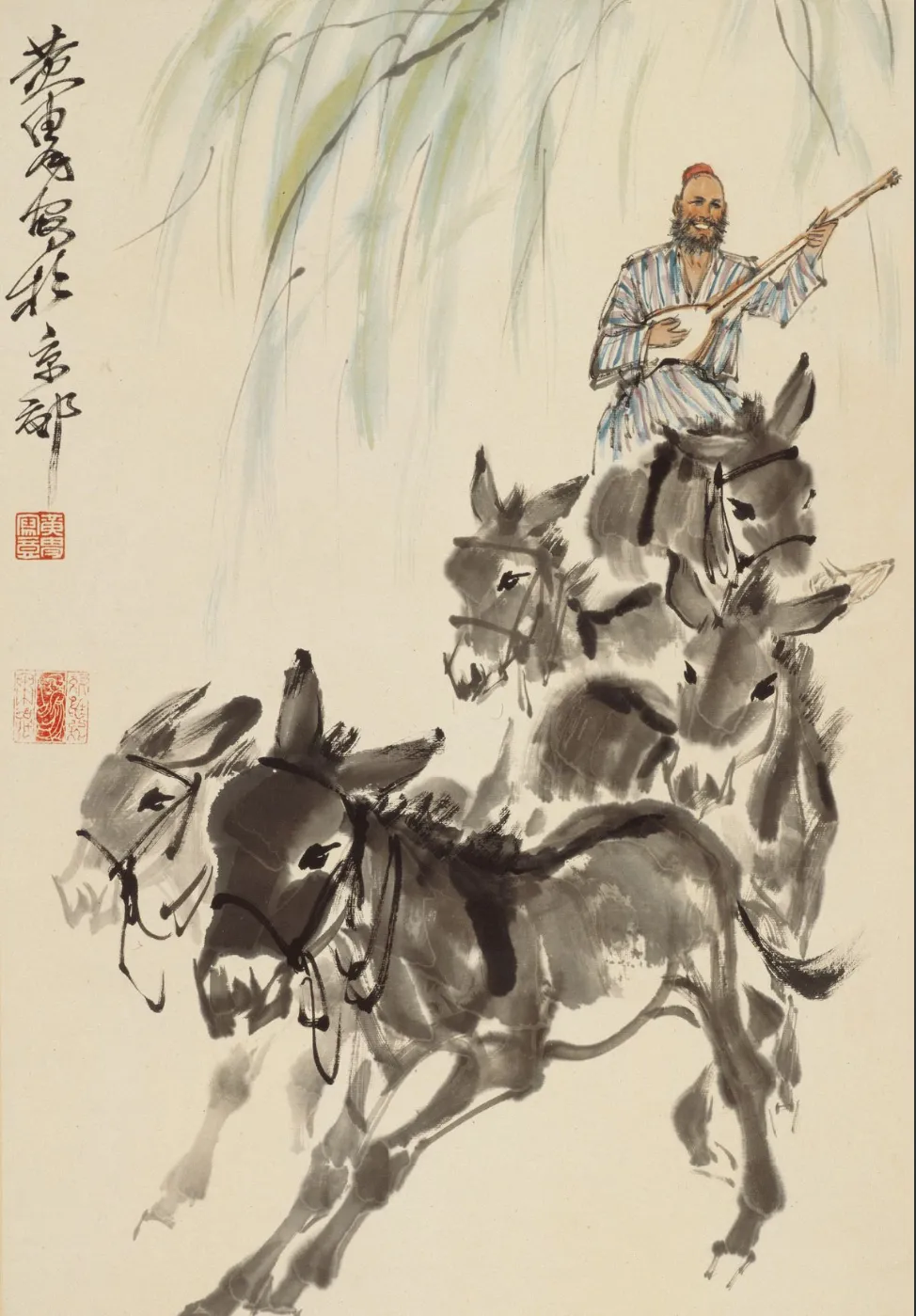

黄胄人物之绘,线条奔逸,若龙蛇飞舞;色彩热烈,如丹霞漫天。其所创格调,前所未有,豪放欢快,情韵交织,氛围浓郁。于少数民族题材,奠时代审美基调,乐观、豪迈、激昂、奋发,启一代人对边疆与少数民族之想象。黄胄与新疆民众情深意厚,屡作速写,捕捉牧民生活之生动瞬间,成真实感人之画卷。其速写恣情纵意,一笔未尽,再添一笔,于反复锤炼间,创“复线式”艺术语言。黄胄常言:“画者感于心,形于手,须立时绘之,务求完备,主题、人物、环境俱臻详尽。”

In Huang Zhou’s figure paintings, the lines are dynamic, like dragons and snakes in motion; the colors are vibrant, like clouds at dawn. The style he created was unprecedented, combining boldness and joy, intertwining emotions, and creating a rich atmosphere. In his works on ethnic minorities, he established an aesthetic foundation that was optimistic, bold, passionate, and vigorous, inspiring a generation’s imagination of the frontier and ethnic minorities. Huang Zhou’s close interactions with the people of Xinjiang resulted in numerous sketches capturing lively and poignant moments of the herders’ lives, forming realistic and touching art pieces. His sketches were expressive and unrestrained; if one line was insufficient to convey the subject’s essence, he would add another, perfecting his “double-line” artistic language through continuous refinement. Huang Zhou often said, “A painter, when truly inspired, must immediately put it on paper and strive to complete the work, ensuring the theme, characters, and environment are detailed and specific.”

观黄胄人物画,工笔之形与写意之神,交融化合。若面容手势,细笔精描;而身段衣纹,寥寥数笔,半工半写,收效斐然。其“逸笔”之意,迥异于古之文人“逸笔草草,不求形似,聊写胸中逸气”,而为写生笔意,关注世情人生。此乃现代人物画由旧时向新时之迁变,亦笔墨由雅趣转向现实之符。

Observing Huang Zhou’s figure paintings, one sees a harmonious blend of meticulous form and expressive spirit. Facial features and gestures are rendered with fine detail, while the body and clothing are depicted with a few strokes, achieving a balance between precision and spontaneity with excellent artistic effect. This interpretation of “freehand brushwork” differs from the traditional literati painting’s “casual strokes, not seeking likeness, but expressing inner spirit,” instead focusing on the themes of social life and realism. This transition marks the evolution of modern figure painting from the old to the new era, and the shift of brush and ink from literati elegance to realistic representation.

黄胄之艺,历早中后三期。初期,形象鲜活,较为纯朴,与古法相近,笔墨淋漓,形神兼备,意趣高雅;中期墨色浓烈,形象逼真,气魄宏厚;至晚,则益以速写之法融于画中,笔墨欢脱,挥洒自如,自成一格,别开生面。

Huang Zhou’s art spans three periods: early, middle, and late. In his early works, the imagery is vivid and relatively simple, closely aligned with traditional methods, with vigorous brushwork and a harmonious blend of form and spirit, rich in artistic flavor; in the middle period, the use of ink and color became intense, with realistic imagery and a pursuit of grandeur and vigor; in the late period, he increasingly incorporated sketching techniques into his paintings, with joyful and free-flowing brushwork, creating a unique and distinctive style.

黄胄者,伴新中国而起,艺坛独步,地位崇隆。毛泽东赞曰:“黄胄,乃新中国所培之有为青年,能画吾人民。”其创作立基于新时期革命与社会变革之洪流,根深传统,然逾其羁绊,持己鲜明风格,兼汲传统绘画之精妙笔法与意趣。于古今交汇之际,融西方写实技法与华夏写实精神、写意之追求,抱“只攻不守”之志,潜心研学,认知渐臻成熟,遂于明晰之理念导引下,成自家独特之艺术风貌。

Huang Zhou, emerging with the rise of New China, stood as a singular figure in the art world with a lofty status. Mao Zedong praised him, saying, “Huang Zhou is a capable young painter nurtured by New China who can paint our people.” His creations were rooted in the revolutionary and social changes of the new era, based on a profound traditional foundation yet transcending its constraints. While maintaining his distinctive style, he also drew from the exquisite techniques and aesthetic interests of traditional painting. At the intersection of tradition and modernity, and the integration of Western realism, Chinese realism, and freehand painting ideals, he embraced the ethos of “constant attack and no defense,” dedicated to continuous learning and exploration, achieving a mature and refined understanding, thereby forging his unique artistic style under clear conceptual guidance.

责任编辑:苗君