陈向迅,生于丙申年杭之江南,擅山水、花卉,名震中青墨坛。其人兼收并蓄,既渴求现代之新,亦不弃古法之意,步步稳健,不乏探索之志。其绘事虽形胜于意,然情不轻抛,符号意旨,未曾遗忘。虽理胜于情,然直觉尤敏。水墨之道,需勇者闯,亦需智者探,形神兼备者,最有望登高。

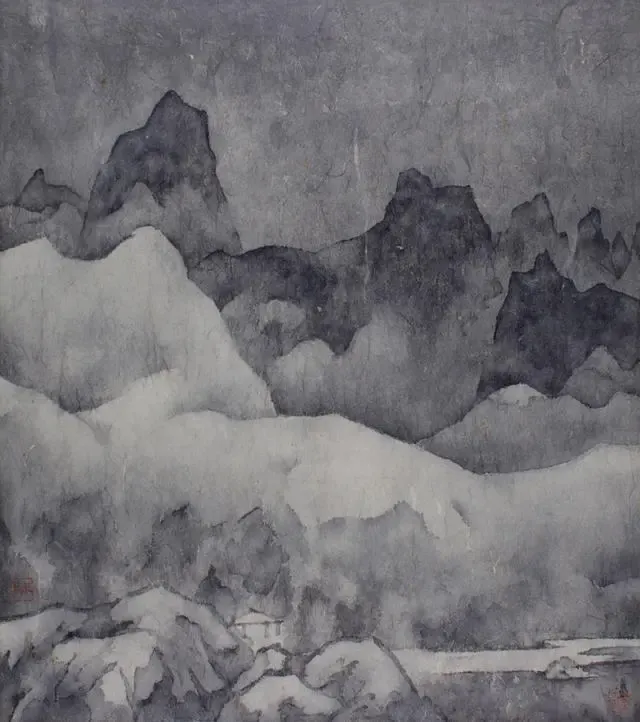

观其画作,木影森然,笔法多变,树姿或夸张,得皴法之妙,显江南林木之盛。陈氏云,画树者,欲传江南气韵,生命蓬勃。其创作热忱,正如树木之姿,自然天成,胸怀广阔。以严肃之态度,自信之神采,立于江南天地之间,为墨道开辟无尽可能。其行将远,前路旷大,艺境愈升,不停息也。

陈向迅之作,烙浙江国画之痕,尚形式与笔墨,崇文人画之道。然其离新浙派守实之风,亲变形与表现。保前辈韵味之喜,弃程式依循。知古人笔墨难越,故以分解孤立强化之策,析前人形式,孤立其要,强化夸张,融己新构。

自甲子年起,陈向迅之作数变,每变皆为探索与自省。其变非随风之仿,乃深思熟虑之果,严肃实验之成。每创皆凝全力,非偶发而成,乃经年思考之作。己巳年,陈向迅作“文字绘画系列”,融文字与山水、拓印与书写于一体。文字入画,虽有前人尝试,向迅不重指意,不独赏其构成,视文字为肌理,与山水浑然相融,古字如拓碑,冥合山水,沉古之感自生。

陈向迅明写意品格乃画之精神,蕴国画精髓。《庄子》论“语贵意”,王维言“意在笔先”,郭熙评“画见大意”,皆重意境之写,以达山水正气。写意为中国画通观要义,立于内容与形式之上。画之发展,写意品格为关键,其信心根于历史。韩愈倡“师意”,为传承与变革明方向。掌写意,当广意精写,方赋画作厚重品格。笔墨有道,历代经典启示尤深。人物、山水、花鸟各有其形式特质,写意笔墨,乃画中精髓。追求写意,源自状物之意,梅兰竹菊、锥画沙、屋漏痕、折叉股,皆写意之至要。

陈向迅以为,画道之评,笔墨独立,写意与笔墨相依。写意须与笔墨契合,内涵形制相合,故于今时画作,写意为先,笔墨为要。品格重笔墨,乃画中尊道。此道廓清画理,品格高下,气象大小,情趣雅俗,赏识深浅,皆以写形至写心为旨。写意为手段,品格为方向,境界为追求,终归“心画”至境,写意品格之塑,乃画作之关键。

写意之“写”,乃笔墨自娱,心手互观,内观“以大观小”,外览“远观其势”,成独立审美。心与迹合,生发意趣。意或单纯,或丰盈,笔墨构思,归于心意之表,则形为其载体。形者,写与意之媒,画中形非自然之貌,景中物非画中之象。欧阳修言“画意不画形”,写形在意,写意在神,神需创,此乃画之意志,尤重形意间之笔墨传达。无笔无意,无形无笔,写意即写形之提炼,笔墨之概括,形象裁剪取舍,自成不言追求。

陈向迅深悟,写形定“意”,笔墨塑品,形与墨相依,求形神兼备。写意之道,主观能动,行笔落墨,内省而成,形意相融,心语独行。故“意”可大论品格,亦细品笔墨。意之品评,外向交流,写与意相辅。自“意在笔先”至“画尽意在”,如杜甫言“意匠经营”,此经营为品而备。写意从心至品,品格之定,归于境界。境者写意之极,意存艺,境涵文,精神归升华,境界托理想。向迅信,境者心造,物虚心实,境差在心。唯品格观照,境界启崇。倪云林山水,淡忧化笔,境幽气雅。写意取境,境存心中,心意定品。境界如潘天寿言:“一步一重天。”咫尺之地,穷生以求,此写意品格之极致愿望。

Translation

Chen Xiangxun: With a Heart Embracing Infinite Possibilities, Seeking Meaning Through Unique Brushstrokes

Chen Xiangxun, born in the year of Bing Shen in Jiangnan, Hangzhou, is skilled in landscapes and floral painting, earning him renown in the middle-aged and young ink painting circles. He embraces both modern innovation and traditional methods, progressing steadily while maintaining a spirit of exploration. His works prioritize form over sentiment, yet never lose their symbolic intent. His rationality often surpasses emotion, though his intuition remains keen. The path of ink painting requires both courage and wisdom; those who master both form and spirit are most likely to achieve greatness.

Observing his works, one finds dense shadows of trees, varied brushstrokes, and exaggerated forms, all capturing the essence of Jiangnan's lush forests through the subtle art of texture strokes. Chen himself says that in painting trees, he seeks to convey the vibrant spirit and abundant life of Jiangnan. His creative passion, much like the trees he paints, is natural and expansive. With a serious attitude and confident demeanor, he stands amid the landscapes of Jiangnan, pioneering endless possibilities in ink painting. His journey is far-reaching, with ever-expanding artistic horizons, moving forward without pause.

Chen Xiangxun's works bear the mark of Zhejiang's traditional Chinese painting, valuing form and brushwork, and upholding the literati painting tradition. However, he departs from the New Zhejiang School's strict adherence to realism, embracing transformation and expression instead. While he retains the charm of his predecessors, he abandons rigid formulas. Aware of the difficulty in surpassing ancient masters in brushwork, he adopts a strategy of deconstructing, isolating, and intensifying certain elements, integrating them into his own new structures.

Since the year of Jiazi, Chen Xiangxun's works have undergone several changes, each being a result of exploration and self-reflection. These transformations are not mere imitations of trends but are products of deep contemplation and rigorous experimentation. Each creation is a concentrated effort, not a spontaneous act, but rather a work shaped by years of thought. In the year of Jisi, Chen created the "Text and Painting Series," integrating text with landscapes, rubbing effects with brushstrokes. Although previous artists had attempted to incorporate text into paintings, Chen does not emphasize the literal meaning of the words, nor does he admire them as separate compositions. Instead, he treats text as texture, blending it seamlessly with the landscapes, where ancient characters merge with misty mountains, evoking a profound sense of antiquity.

Chen Xiangxun understands that the essence of freehand brushwork lies in the spirit of the painting, embodying the core of Chinese art. Zhuangzi speaks of the value of intention in words, Wang Wei emphasizes "intention before brushwork," and Guo Xi critiques "seeing the grand idea in painting," all highlighting the importance of capturing the spirit in landscapes to convey their true energy. Freehand brushwork is the overarching principle of Chinese painting, founded on both content and form. The development of a painting hinges on the character of freehand brushwork, its credibility rooted in history. Han Yu advocated "learning the essence," guiding both tradition and innovation. Mastery of freehand brushwork requires broadening intention and refining execution, endowing the work with profound character. The language of brushwork, deeply inspired byical works, holds the essence of figure, landscape, and bird-and-flower paintings. The pursuit of freehand brushwork arises from the intention to depict objects, where elements like plum, orchid, bamboo, chrysanthemum, as well as techniques like "carving on sand," "roof leak marks," and "broken fork stroke" are all vital to the art of freehand painting.

Chen Xiangxun believes that in the evaluation of painting, brushwork should be unique, with freehand brushwork and brush techniques interdependent. Freehand brushwork must harmonize with brushwork, ensuring that the content and form are aligned. In contemporary painting, freehand brushwork is paramount, with brushwork being essential. Emphasizing brushwork is a respected principle in painting, clarifying the logic of art, distinguishing between different levels of character, scale, taste, and depth of appreciation. The goal is to move from "writing form" to "writing the heart." Freehand brushwork is a means, character is the direction, and the ultimate goal is to reach the realm of "heart painting." The creation of freehand brushwork character is crucial to the work.

The "writing" in freehand brushwork, for Chen Xiangxun, is an enjoyment of brush and ink, where the heart and hand mutually observe. It involves an inner contemplation of "seeing the large in the small" and an outer observation of "perceiving the overall force," forming an independent aesthetic. When heart and traces merge, meaning arises. The intention may be simple or abundant, but brushwork and ink ideas always express the artist's inner feelings, with form as their vehicle. Form serves as the medium between writing and meaning; in the painting, form does not mimic nature, nor do the objects depicted equate to their real counterparts. Ouyang Xiu said, "Paint the meaning, not the form," indicating that writing form conveys intention, and intention embodies spirit. The spirit requires creativity, which is the essence of painting, particularly emphasizing the brushwork that conveys both form and meaning. Without brushwork, there is no intention; without form, there is no brushwork. Freehand brushwork is the distillation of form and the summarization of brushwork, where the adjustment and selection of imagery naturally lead to an unspoken pursuit.

Chen Xiangxun deeply understands that writing form determines meaning, and brushwork shapes character, with form and ink interdependent, seeking the unity of form and spirit. The path of freehand brushwork lies in subjective effort, with each stroke and ink drop formed through inner reflection, where form and meaning merge, and heart speaks through the brush. Thus, "meaning" can be broadly discussed as character, or finely as brushwork. The evaluation of meaning involves outward interaction, with writing and meaning supporting each other. From "intention before brushwork" to "painting exhausts intention," as Du Fu said, "The artist painstakingly crafts," this effort is prepared for character. Freehand brushwork evolves from mind to character, where the determination of character ultimately leads to the realm. The realm is the pinnacle of freehand brushwork, where meaning resides in art, the realm embraces culture, and the spirit ascends, driven by ideals. Chen believes that the realm is created by the heart; the material is illusory, the heart real, with the realm's difference rooted in the heart. Only through character's perspective can the realm inspire reverence. Ni Yunlin's landscapes, with their faint melancholy, transform into brushstrokes of deep meaning, the realm serene and elegant. Freehand brushwork seeks the realm, the realm exists in the heart, and heart intention defines character. As Pan Tianshou said, "Each step is a new heaven." Even within a small space, a lifetime's effort is required to seek it, making this the ultimate aspiration of freehand brushwork's character.

责任编辑:苗君