杨晓阳,戊戌年生于陕西,习绘事于西安美院国画系,承教刘文西。初期绘风写实,继承刘氏与黄土画派质朴风格,然脱“文革”虚饰,返生活之真,与其豪放而内敛之性相应。

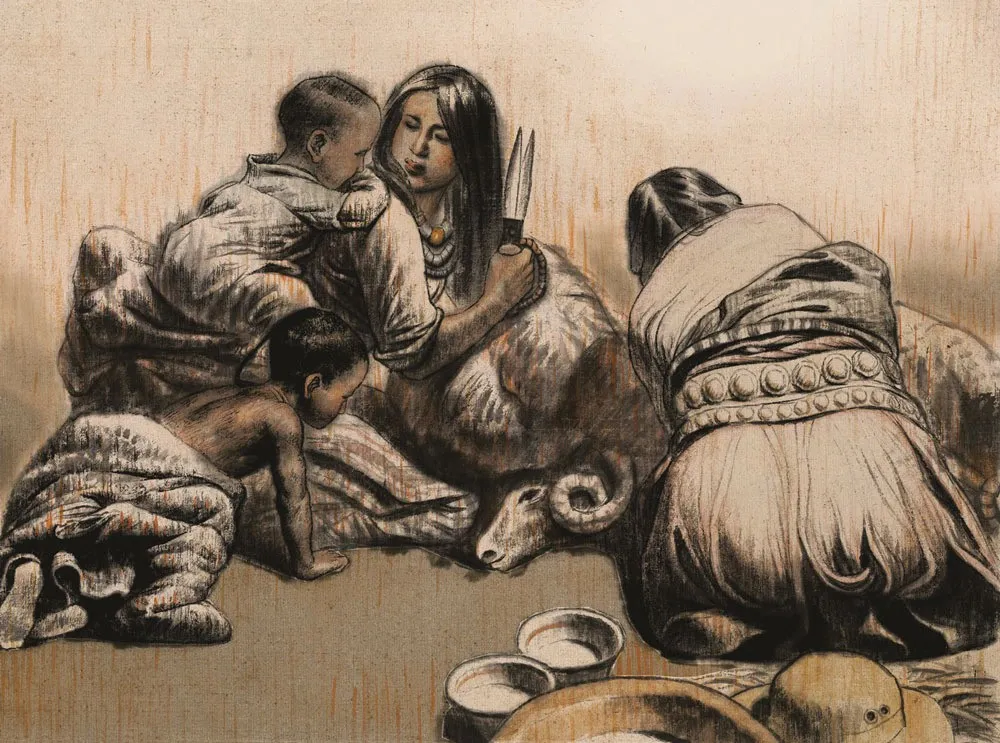

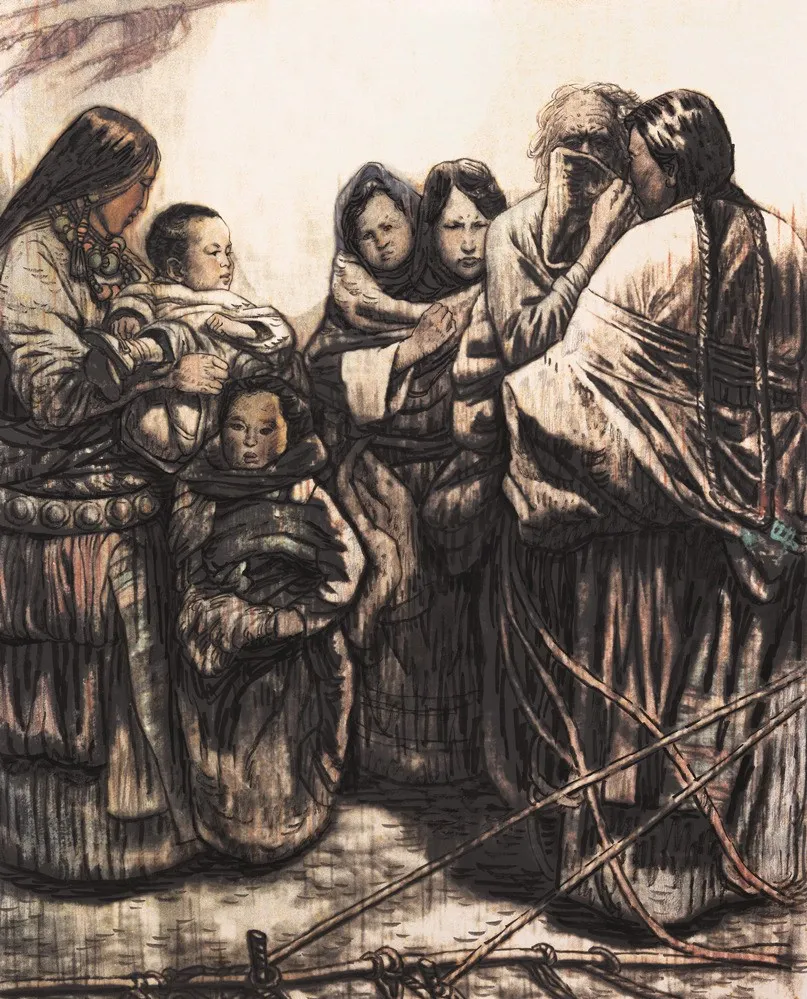

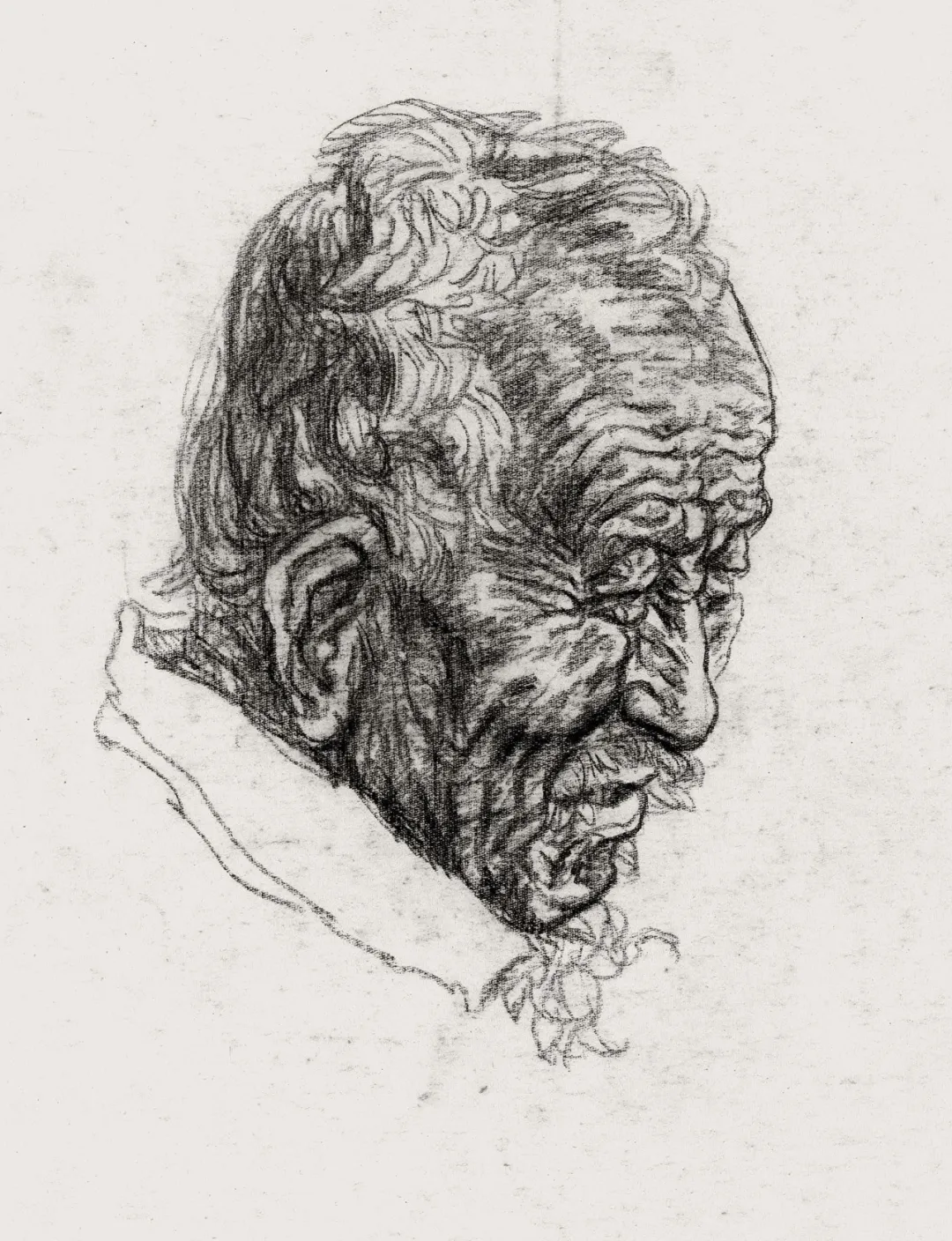

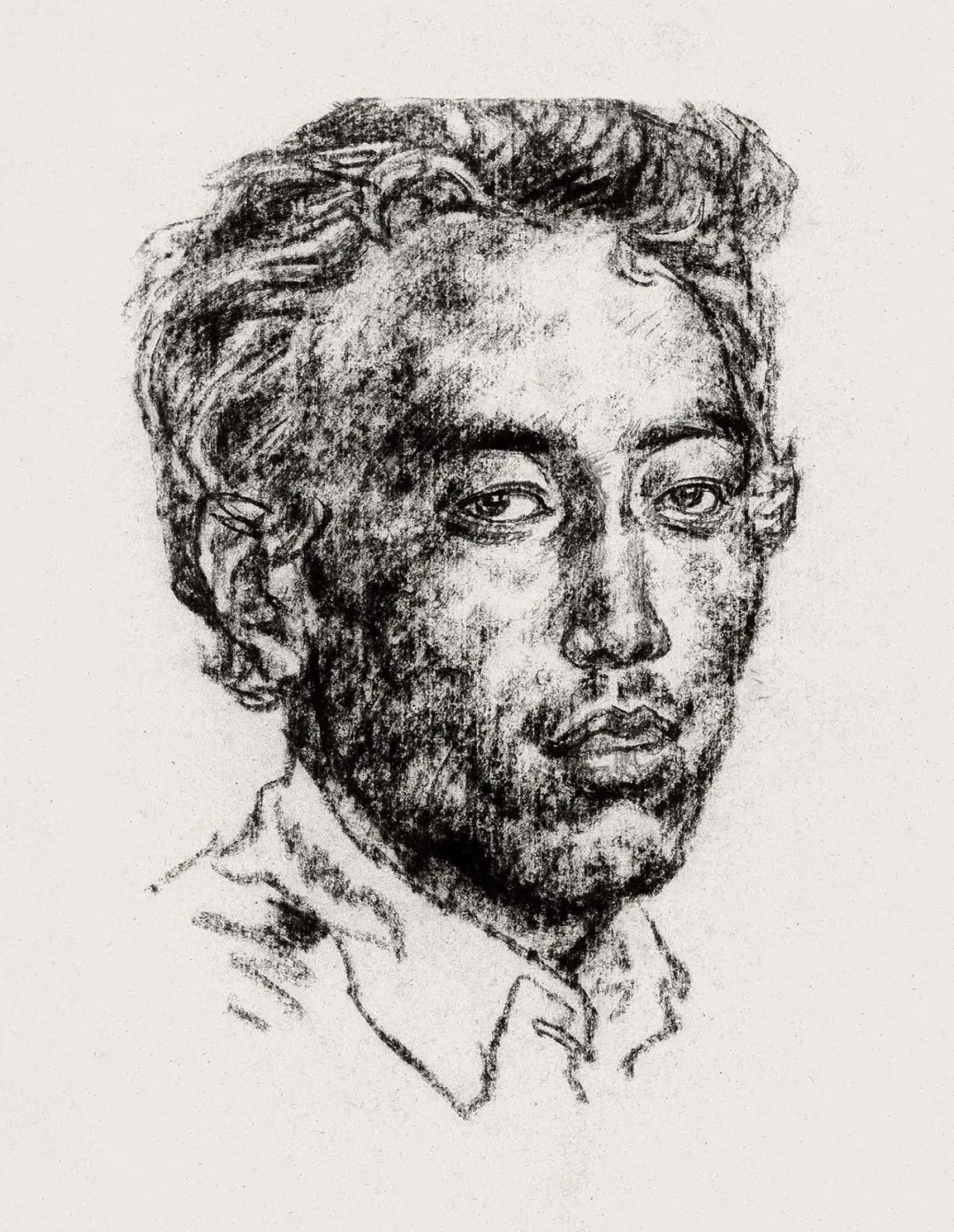

杨晓阳常言,其学画历程,未失一课。工笔、写意、小写意、大写意,淡彩、重彩、写实、变形、概括,及至泼墨,皆历步履,无一略过。壬戌年,赴陕北绥德、米脂、吴堡乡野,亲历黄河船工生活而取材甚丰,遂成《黄河艄公》与《黄河的歌》二作。前者老船工形如铁铸,线条粗犷,笔墨奔放,力道强烈;后者背景山河宏伟,唢呐声中乡亲神情细腻,光影交织,情感深邃。

《黄河艄公》

《黄河的歌》

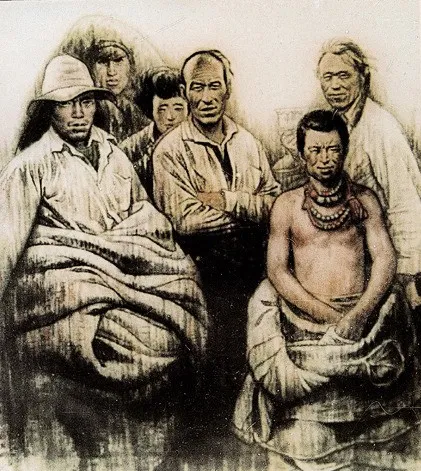

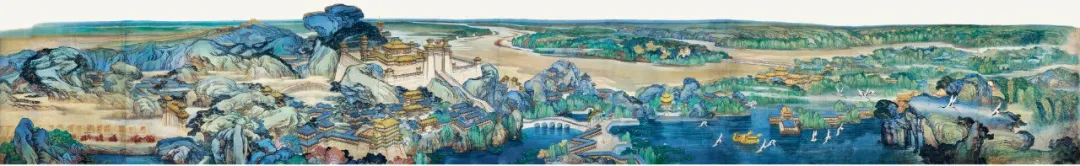

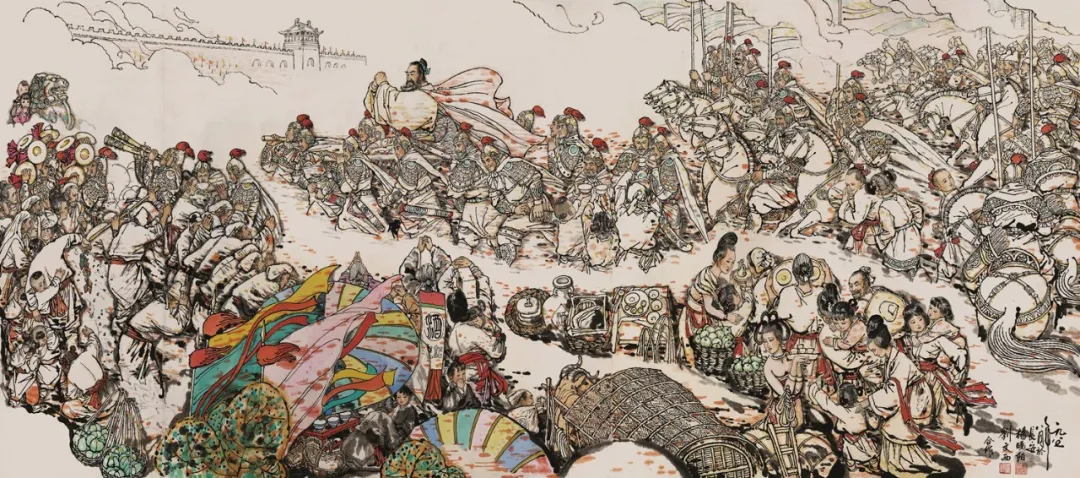

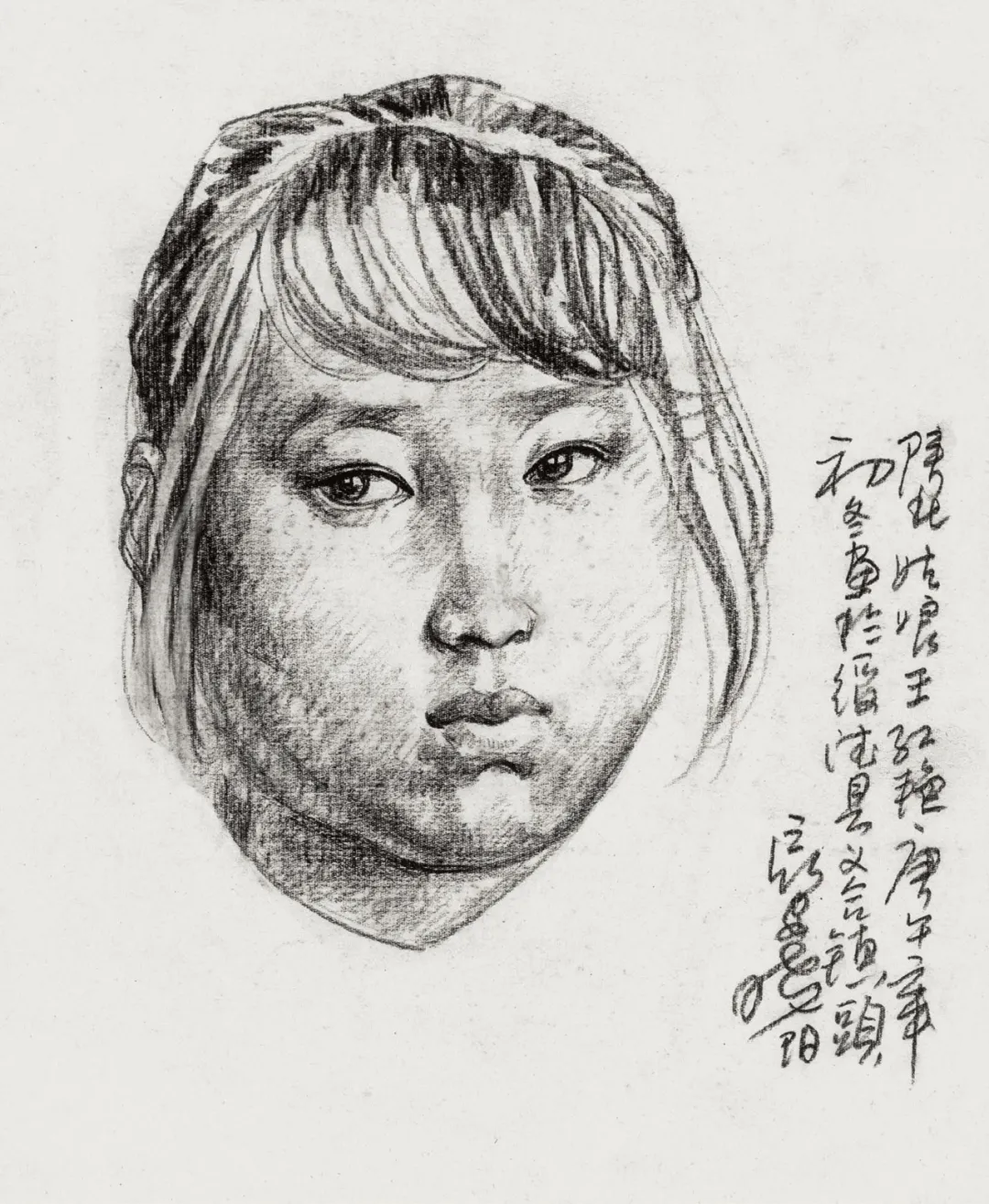

杨氏画风不固一格,恒求新变。乙丑年,与同学结伴自长安骑行,重走丝路,考察石窟艺术,独行至新疆腹地,访拜城克孜尔、库木吐拉石窟,取材丰厚。丙寅年,创《大河之源》组画,取西洋明暗素描之法,青藏高原人物形象圆润厚实,具西方石版画效果。与刘文西合创《黄巢进长安》,画卷宏伟,笔墨兼工带写,已离纯写实之道。杨氏主攻人物,兼善山水。为西北饭店绘《阿房宫赋》壁画,采工笔重彩与青绿山水之法,构图借杜牧《阿房宫赋》与建筑史料,画面饰韵充盈。

二十世纪九十年代,杨晓阳壁画创作臻巅。其代表作《丝绸之路》构图超越时空,显中华文明与西方文化交融之势。乙亥年,作八十米壁画《生命之歌》,将中国线描技法运至极致,古今人物以简洁线条勾勒,融于繁复饰图之中。

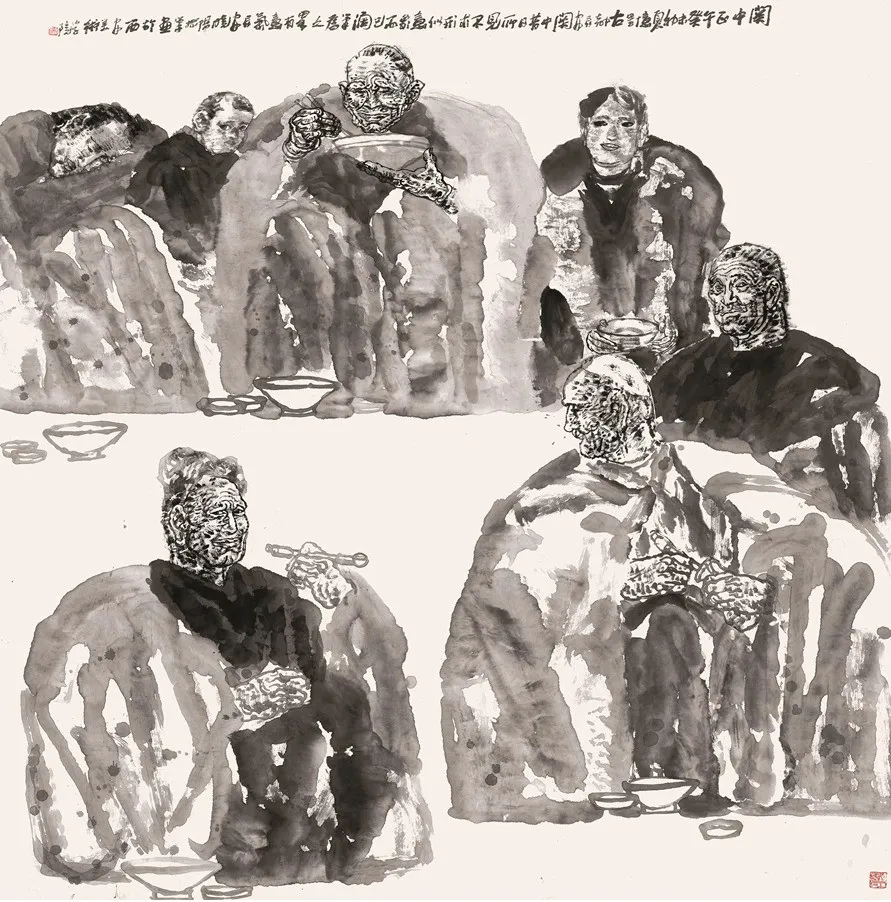

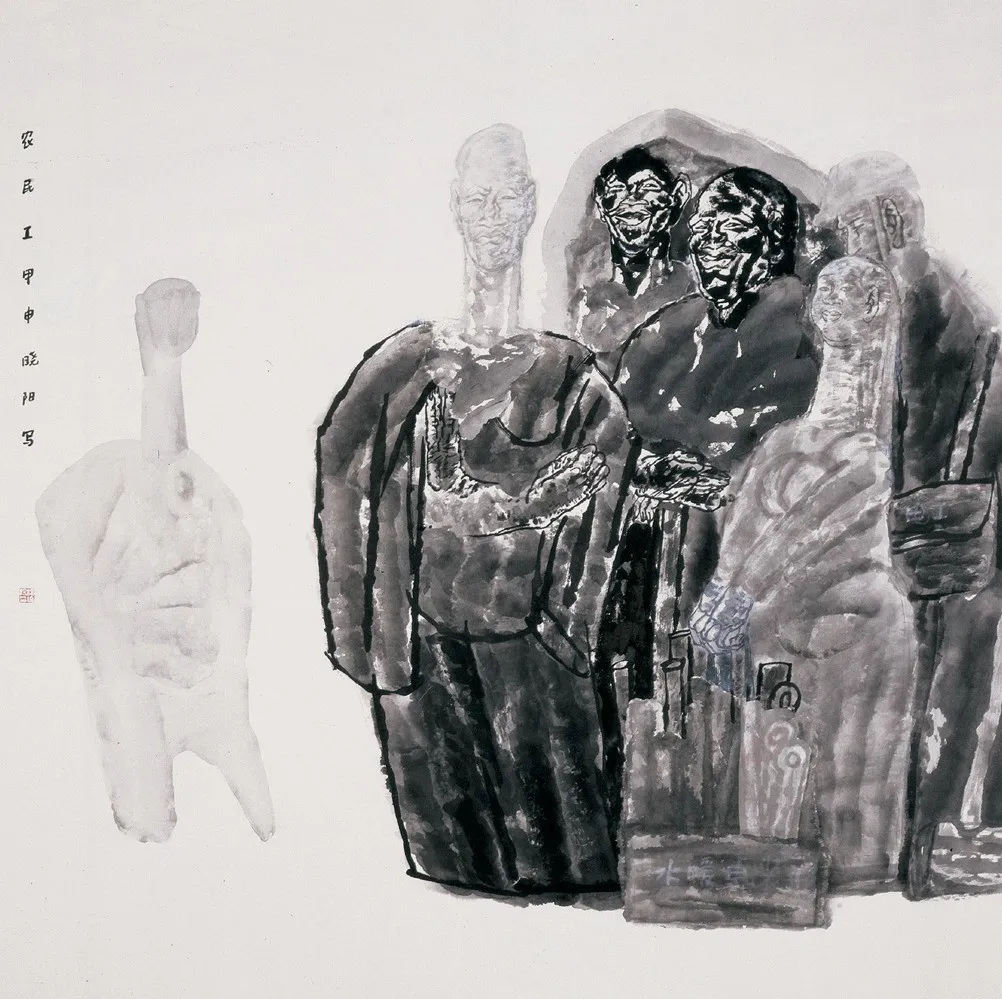

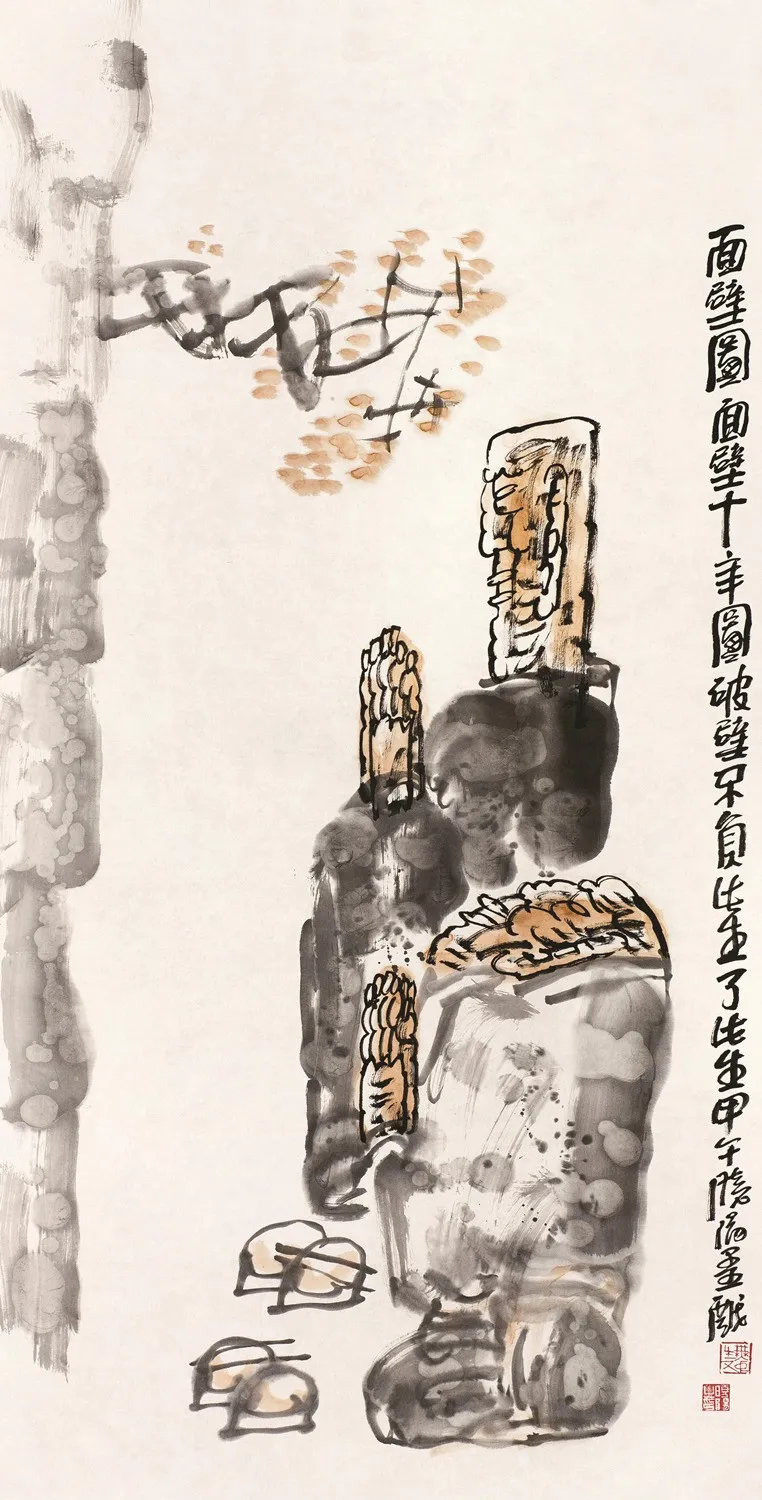

迈入二十一世纪,杨晓阳画风自饰趋意,由繁入简,渐至大写意之境,若蜕茧而出,创作自由由此而得。其笔下古人,如《面壁图》《品茗图》者,气象豪迈,仕女如《最是一年春处好》《母子情深》者,仪态端庄。因深谙陕北农民之生计,所作《关中正午》《农民工》诸图,皆具淳朴之风。另作《雪域》以写藏民生活,人物或虚或实,虚实交错,相映成趣。

杨晓阳论画,谓中国画分五境:形、神、道、教、无。形乃艺之根本,神为形中之采,道为艺之源,教为道之传,而无为艺之极致,超越形迹,臻于自在。杨氏言,大写意非止技法,实乃精神与观念之融。须以广阔视野观照世界,通达艺道全貌。此理超越西洋之形,重于象外之提炼升华,乃中国艺术独特之造型观。

杨晓阳经年实践与思考,归纳出独特之“大写意”法则,创立“十观法”。大观小,小观大,远观近取,近观远取,助画者于宏微之间求得平衡。更归纳勾勒、泼墨、破墨、积墨诸技,使画者于表现中臻至深邃意境。

杨氏以为,大写意不止为创作之途,乃艺境巅峰所在,须画者恒探精研,步步深索,自写实而至写意,由写景而达写心,终臻高远普遍之境。杨氏笃信,中华写意独立寰宇,光暗并存,正因此纷纭多姿,方铸艺之独韵。嘱吾辈审艺脉,明艺史,于新时代共推中华艺道昌盛。

Yang Xiaoyang: Realism in Style, Embracing Simplicity, Balancing Form and Spirit with Grandeur

Yang Xiaoyang, born in the Wuxu year in Shaanxi, studied at the Chinese Painting Department of Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts under the guidance of Liu Wenxi. His early painting style was realist, inheriting the simplicity of Liu and the Yellow Earth School, while breaking away from the superficiality of theCultural Revolution, returning to the truth of life, reflecting his bold yet reserved nature.

Yang Xiaoyang often stated that throughout his learning process, he never missed a lesson. From meticulous gongbi to xieyi, small to large xieyi, light to heavy colors, realism to deformation, abstraction, and even splashed ink techniques, he methodically progressed through every stage. In the Renxu year, he traveled to the rural areas of northern Shaanxi, experiencing the life of Yellow River boatmen firsthand, gathering abundant material, which led to the creation of "Boatmen of the Yellow River" and "Song of the Yellow River." The former depicts a boatman as strong as iron, with rough lines and bold ink, exuding immense power; the latter, with a grand mountainous background, captures the delicate emotions of villagers immersed in the sound of the suona, with intertwined light and shadow, expressing deep feelings.

Yang's style is not confined to a single approach; he constantly seeks new changes. In the Yichou year, he and hismates cycled from Chang'an, retracing the Silk Road, studying grotto art, and he traveled alone deep into Xinjiang, visiting the Kizil and Kumtura Caves in Baicheng, gathering rich materials. In the Bingyin year, he created the "Source of the Great River" series, using Western chiaroscuro techniques, rendering the figures of the Tibetan Plateau with roundness and solidity, evoking the effect of Western lithographs. His collaboration with Liu Wenxi on "Huang Chao Enters Chang'an" produced a grand historical painting, with brushwork that blends meticulousness and freehand, moving beyond pure realism. Yang specializes in figure painting but is also skilled in landscapes. He painted the "Rhapsody of Epang Palace" mural for the Northwest Hotel, using traditional gongbi heavy color and green landscape techniques, drawing on Du Mu's "Rhapsody of Epang Palace" and architectural history sources, resulting in a richly decorative composition.

In the 1990s, Yang Xiaoyang's mural work reached its zenith. His representative work, the "Silk Road" mural, employs compositions that transcend time and space, showcasing the integration of Chinese civilization with Western culture. In the Yihai year, he created an 80-meter mural "Song of Life" , where he pushed Chinese line drawing techniques to their limits, using simple lines to outline figures from ancient and modern times, blending them into complex decorative patterns.

Entering the 21st century, Yang Xiaoyang's style evolved from decorative to expressive, simplifying complexity and gradually entering the realm of large-scale xieyi, like breaking out of a cocoon, thus gaining creative freedom. His portrayals of ancient figures, such as in "Facing the Wall" and "Tea Tasting," are grand and vigorous; his depictions of elegant ladies, as in "Spring's Best Moment" and "Deep Maternal Love," are stately and graceful. His deep understanding of the lives of northern Shaanxi farmers enabled him to create works like "Noon in Guanzhong" and "Migrant Workers," which exude simplicity and honesty. Additionally, his works like "Snow Region" depict Tibetan life, where figures are treated with a mix of realism and abstraction, creating a fascinating interplay of contrasts.

Yang Xiaoyang's philosophy of painting posits that Chinese art has five realms: form, spirit, path, teaching, and nothingness. Form is the foundation of art, spirit is the essence of form, the path is the source of art, teaching is the interpretation of the path, and nothingness is the ultimate realm of art, transcending form and nothingness to attain freedom. Yang believes that large-scale xieyi is not merely a technique but embodies spirit and concept, requiring an artist to view the world with a comprehensive perspective, mastering the entirety of artistic principles. This concept surpasses Western notions of form, emphasizing the refinement and sublimation of "image," which is the unique view of Chinese art.

Yang Xiaoyang, through years of practice and reflection, developed a unique methodology for large-scale xieyi, creating the "Ten Observations," including seeing the small in the large, seeing the large in the small, distant views with close details, and close views with distant perspectives, helping artists find balance between macro and micro scales. He also categorized techniques such as outlining, splashed ink, breaking ink, and accumulating ink, enabling artists to reach deeper levels of expression.

In Yang's view, large-scale xieyi is not just a creative process but represents the pinnacle of artistic achievement. It requires the artist to engage in continuous exploration, moving from realism to xieyi, from depicting scenes to expressing the heart, ultimately reaching a sublime level of universal significance. Yang firmly believes that Chinese xieyi art holds the highest place in world art; though it embodies both light and shadow, it is precisely this complexity that defines the unique charm of Chinese art. He urges the nation to elevate its understanding of art, properly grasp the threads of art history, and thus propel Chinese art towards greater prosperity in the new era.

责任编辑:苗君